Innocent Georgia Man Exonerated of Rape, Kidnapping and Robbery After 17 Years Imprisonment

By Hans Sherrer

For

Justice:Denied

magazine

In 1987 Clarence Harrison was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for the October 25, 1986 kidnapping, rape and robbery of a 25 year-old-woman waiting at a bus stop in Decatur, Georgia, who was also robbed of her watch and money. Clarence was 27 years old. Although she was attacked at 6am, before dawn, the jury relied on the woman’s identification of Clarence out of a photo lineup and her courtroom ID of him during his trial. Testing of the seminal fluid collected from the victim was only able to narrow her attacker to 88% of the male population. The police initially fingered Clarence as a suspect because he lived in the area of the attack, and he had served five years in prison after being convicted at 19 of armed robbery.

Determined

to prove his innocence,

Clarence at first spent all his spare time in prison diligently

working on his case. As he recently said, “I worked on my

case so

much I got

migraine headaches.” 1

However after encountering the setbacks of having his direct appeal

denied, and having a private lab determine in 1988 that the

attacker’s semen sample was unsuitable for DNA testing,

Clarence

began to despair: “After a year or so, you get burned out and

you

fall off into the system and you lose faith and your hope and you

begin to believe you’ll never get out. And that happened to

me.” 2

Denied parole, and unlikely to be granted it without accepting responsibility for a heinous crime he didn’t commit, Clarence languished in prison. A turning point came in 1997 when a young fellow prisoner talking to his girlfriend on the telephone, unexpectedly handed Clarence the phone: On the other end was the young woman’s mother, Yvonne Zellers. Yvonne offered to write Clarence, but he resisted because at that point it appeared he would die in prison. Clarence finally agreed she could write him about what she learned from the Bible, and she soon began to visit him. A year later he asked Yvonne if she would marry him if he was ever released from prison. She said yes, and Clarence had a renewed reason to fight for his exoneration.

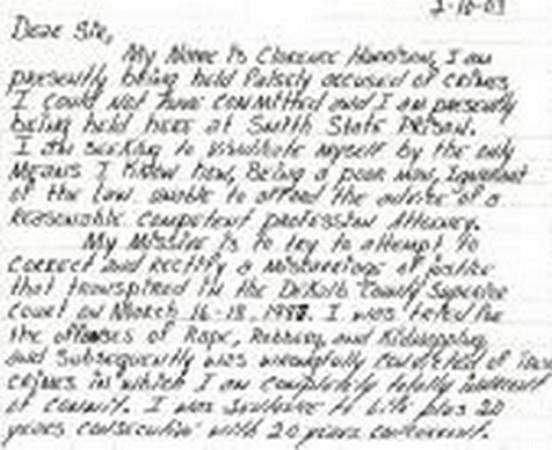

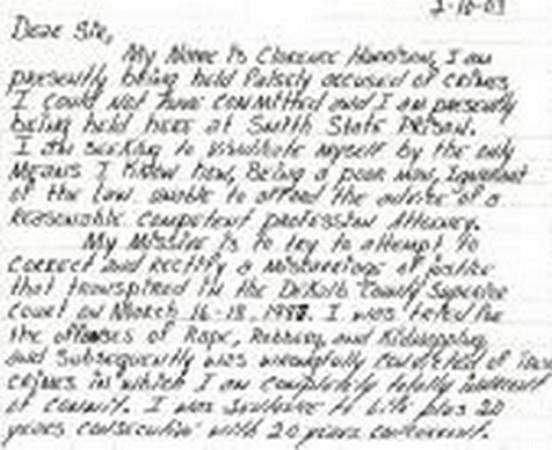

After years of pursuing various leads, on February 10, 2003 Clarence wrote a letter to the newly formed Georgia Innocence Project (GIP) that began: “My name is Clarence Harrison. I am presently being held falsely accused of crimes I could not have committed.”

On August 24, 2004, the semen’s testing by a private laboratory in California, Forensic Science Associates, excluded Clarence as the women’s attacker. A week later, on August 31st, Judge Cynthia Becker granted Clarence’s motion for a new trial and then dismissed the charges. Clarence was immediately released from custody. On the DeKalb County courthouse steps, the same courthouse where 17 years earlier he had wrongly been found guilty and sentenced to life in prison, Clarence Harrison credited his fiancé Yvonne with giving him the renewed hope that led to his exoneration. He also said he hopes to work with the GIP to help free the many innocent men that he believes he left behind in prison. Clarence also mention Yvonne and he would marry as soon as could afford to buy a ring. Within days, strangers stepped forward and donated such things as rings, a cake, and a singer for their wedding. Several business owners also called to offer Clarence a job.

Although

it is unknown how much the

victim was influenced by the Decatur police and DeKalb

County's D.A. to wrongly identify Clarence as her attacker during the

initial

photo line-up, and then at his trial, he holds no enmity towards her.

After his release he said, “I never held any anger toward

her. I

just thought she made a mistake.” 3

Emory Law Student Helps Free Georgia Man Imprisoned For 17 Years

By Georgia Innocence Project (Press release, September 3, 2004) (500 words)

Jason Costa, 21, is still reeling from the release of Clarence Harrison, who spent more than 17 years in prison for a crime he did not commit. Harrison, 44, was freed on August 31, 2004 after DNA test results ruled him out as the perpetrator of a rape for which he was convicted in 1987.

Costa, an Emory Law School student, started an internship with the Georgia Innocence Project (GIP) in May 2004. The two-year-old organization has received more than 1,400 letters from prisoners asking for help with their cases. GIP has only opened six cases, and Harrison is the first prisoner to be exonerated through its efforts.

“It was the kind of case where we knew we could help him because we expected DNA to be available,” GIP Executive Director Aimee Maxwell said. “There is absolutely no way we would get the work done without the law students. We are a very bare-boned nonprofit, and there is no way I could devote the energy and time on the cases without Jason and others helping.” Others who helped on the case are Emory Law School student Jennifer Walker, 21, Laura Verduci, a Georgia State Law School student, and Emily Gilbert, now a public defender in DeKalb County.

The case has helped Costa realize his true calling – public interest law. “It was fantastic to help free someone who is innocent. But as great as it was, the real accomplishment is doing the work that we’re doing. This just highlights how important public interest work is,” he said. Costa, president of the Emory Public Interest Committee at the law school, received the Sutherland, Asbill & Brennan grant, which paid his summer salary at GIP.

Harrison first wrote to GIP in February 2003. He was told all evidence from his case had been destroyed, but GIP interns found one slide from the rape kit.

Costa worked with the DeKalb County District Attorney’s Office to allow evidence to be tested by a lab GIP considers the best, Forensic Science Associates in California. Another lab had trouble testing the evidence a few years earlier.

“Jason coordinated going to the prison to take our client’s DNA sample. He watched the Georgia Bureau of Investigation take the sample and made sure the evidence was delivered to the lab,” Maxwell said. It was the first time Costa met Harrison. Although he had communicated with him by telephone and letter.

Costa

and Walker will continue to work

for the GIP. Costa will design and help Harrison implement a plan to

transition to life after exoneration, Maxwell said, including

obtaining a driver’s license, getting a job, and settling

into a

new home.

Costa

and Walker will continue to work

for the GIP. Costa will design and help Harrison implement a plan to

transition to life after exoneration, Maxwell said, including

obtaining a driver’s license, getting a job, and settling

into a

new home.

“Historically when a person has been exonerated, the biggest challenge has been that there is not enough help for the individual to get re-acclimated to society,” Costa explained. “We get to set a new standard on what kind of impact an organization such as GIP can have in an individual’s life.”