“That’s Not My Fingerprint, Your Honor”

Lawyer Saved By The Spanish National Police From FBI Terrorist Frame-up

By Hans Sherrer

Justice:Denied magazine, Issue 25, Summer 2004, pp.

11-14, 19

It is easy to think – “It won’t happen to me” – when one hears of a person wrongly accused or convicted of a heinous crime. However, the lack of critical judicial examination of police agency arrest and search warrant affidavits creates an environment where any one of us at any time can have our life shattered by being falsely implicated in a capital crime. That is the cautionary message of Brandon Mayfield’s saga of how he was wrongly fingered by the FBI as an international terrorist involved in murderous bombings in a country he has never visited.

FBI Affidavit Tagged Brandon Mayfield As A Terrorist

Attorney Brandon Mayfield was arrested by the FBI on

the morning of May 6, 2004 at his office in a

After Mayfield’s

arrest, his wife Mona told reporters, “I think it’s crazy. We haven’t been

outside the country for 10 years. They found only a part of one fingerprint. It

could be anybody.” 7 Her words in defense of her husband were soon to prove

prophetic.

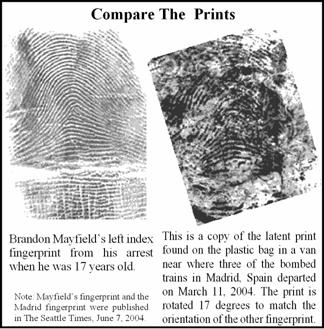

Werder’s affidavit asserts Mayfield was initially targeted as a suspect in the bombing when his print was identified by FBI’s Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS) as one of several possible matches with one of the prints recovered from the plastic bag by the SNP. The affidavit further states FBI examiner Green then manually matched the print of the fourth AFIS match to the Madrid print as belonging to Mayfield, and then the other two examiners referred to in the affidavit verified that match.

Yet in spite of the certainty of the affidavit’s

language tying Mayfield to the Spanish bombing, on May 24th the FBI suddenly

reversed itself by acknowledging his print didn’t match one on the plastic bag,

a federal judge dismissed the material witness warrant, and Mayfield was released

from federal custody. 8

Brandon Mayfield in May 2004 after

his release from being falsely imprisoned as an international terrorist.

Spanish National Police Knew Mayfield Was Innocent

That reversal wasn’t surprising to the SNP. That

agency’s fingerprint analysts reported to the FBI on April 13th – 23 days

before Mr. Mayfield’s arrest – that their comparison of his fingerprint with

the one on the plastic bag was “conclusively negative.” 9 Corroborating that conclusion was

the Spanish government had no record that Mayfield had ever traveled to that

country.

The FBI discounted

the SNP’s assessment to the degree that when the FBI

lab’s Ted Green traveled to Spain in late April to meet with SNP officials to

discuss the bureau’s identification of Mayfield, he didn’t bother to examine

the original print on the bag. 10

However Spanish officials not only

“refused to validate” the FBI’s identification of Mayfield, but they continued

their investigation as if his prints weren’t on the bag. 11

So the SNP’s disagreement with the FBI’s Mayfield match was

grossly misrepresented by the assertion in agent Werder’s

affidavit, “…the SNP felt satisfied with the FBI laboratory’s identification.” 12 That

disagreement became public knowledge when SNP officials announced on May 20th

that they had linked two prints on the bag to an Algerian with a police record

and a Spanish residency permit. 13 The next day a

federal judge in

After Mayfield’s

exoneration on May 24th, the FBI claimed the error was caused by its crime

lab’s reliance on a “substandard” image of the

Federal prosecutors

went beyond the FBI’s assertion that the image was “substandard” by claiming in

a document related to his release, “Using the additional information acquired

this weekend in

Fingerprint Analysis Is A

Pseudoscientific Art

Thus an obvious question is: How can fingerprint

analysis be so unreliable that three FBI experts and an independent analyst

could mistake the print of a mild mannered family man with an expired passport

who has never been to

The first assumption

- that fingerprints are unique – has been accepted on blind faith by courts in

the

The second assumption

– that a person’s fingerprints have unique identifiers that can infallibly be

measured - has likewise not been scientifically proven. Differing methods of

identifying a person by their physical characteristics were developed during

the 19th century. However no scientific basis established the accuracy of any

of them. The British Home Office, e.g., rejected the use of fingerprints for

identification purposes in 1894, because “there was no reason to resort to an

unproven technology like fingerprints.” 22

Fingerprinting eventually enjoyed

widespread adoption because they are easy to obtain, classify, catalog,

retrieve and compare. Thus the adoption of fingerprint patterns as an

identification method was driven by bureaucrats who embraced it as meeting

their work requirements – and who had no concern for the scientifically

unsubstantiated idea they can be measured to unfailingly identify a person.

Expediency continues to be a justification for fingerprinting. Proponents argue

that its common use for 100 years justifies continuing to do so.

The third assumption

– that fingerprint examiners have the skill to infallibly determine if print

samples from different sources originated from the same person – has been

empirically disproven. The many people falsely

implicated in a crime by an erroneous fingerprint ID is consistent with

proficiency tests over the past several decades that have resulted in failure

rates by experienced examiners of over 50%. That lack of expertise is

predictable considering fingerprint analysis is an artful technique that

depends on a human interpreter’s subjective evaluation. In 1892 Francis Galton, one of the fathers of fingerprinting, was honest

enough to write, “A complex pattern [like fingerprints] is capable of

suggesting various readings, as the figuring on a wallpaper may suggest a

variety of forms and faces to those who have such fancies.” 23 One

hundred and ten years later

Since the three assumptions underlying fingerprinting

are unproven or in error, the practice of comparing a suspect’s print with a

crime scene (latent) print is vulnerable to honest and deliberate

misinterpretation, and outright fakery. While a malevolent examiner can falsify

evidence to implicate an innocent person in a heinous crime, an erroneous ID

can be made by a conscientious examiner doing his job in the way he is trained.

This has been borne out both in theory and practice by events on three

continents during the last century.

A 100 Year Tradition of Fingerprint Fakery

In 1913 handwriting expert Theodore Kytka

discovered a process of transferring an innocent person’s fingerprint to an

incriminating object. 28 Prior to that,

French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon faked “two

different fingerprints which ostensibly showed sixteen matching points of

similarity.” 29 Keep in mind that the FBI claimed to have matched “in

excess of 15 points” of Mayfield’s print to the one on the plastic bag. In 1920

chirographer Milton Carlson demonstrated a technique for transferring a

person’s fingerprint to an incriminating object if a photo of the person’s

print was available. 30 Mr. Carlson wrote that it was easier to forge a

person’s fingerprint than their handwriting, since “to complete a perfect

forgery of a finger-print in the exact form is as easy to make as any steel

ruler, surveyor’s tape, or a wheel within a wheel.” 31 In

1923, former Secret Service agent E.O. Brown developed a fingerprint forgery

method so foolproof that he successfully planted a fake print of the

Fingerprint examiners

were so fearful of the danger to the practice posed by investigators and

critics such as Wehde, that at the 1927 national

meeting of the International Association for Identification (IAI), the Ethics

Committee issued a recommendation, “that every possible effort should be made

to checkmate these activities insofar as they may prejudice the public against

latent fingerprints found at the scene of crime as competent evidence in a

criminal trial…” 34

However such public

relations efforts were needed not only to counteract publicity about the

development of fingerprint forgery techniques, but to illuminate the fact that

they were actively being used by police agencies to frame suspects. Two years

prior to the IAI’s 1927 meeting, the FBI identified

the forgery of an alleged crime scene fingerprint by a law enforcement officer. 35 Two

years later, at the IAI’s national meeting in 1929,

it was reported that law enforcement fingerprint forgery schemes had been

uncovered in

The most extensive

known police agency forgery scheme was uncovered in 1992 when it was discovered

that New York State Crime Lab personnel were forging fingerprint evidence. 38 The

subsequent investigation found that at least five crime lab employees were

involved in the forgery ring that faked fingerprint evidence in at least 40

cases, including homicide cases, over eight years. 39 Their forgery techniques included lifting a print from

an inked fingerprint card on file and transferring it to crime scene evidence,

and photocopying an inked print and labeling it as a latent crime scene print. 40

Two of the forgery

ring’s five state police officers convicted of perjury, evidence tampering and

official misconduct, were latent fingerprint examiners certified by the IAI. 41 The

ring’s members admitted they manufactured fingerprint evidence because it was

so easy to do, and get away with doing. Investigators wrote in the official

report to

As common as

fingerprint forgery is known to have occurred in the past, the falsification of

fingerprint evidence has been exponentially eased by the computerization of

fingerprint images by police agencies, including the FBI. In a November 2003

article, Wired magazine explored how easily a

digitized image such as a photograph can be altered to be indistinguishable as

a fake, using off the shelf software. 44

It is also known that the fingerprints in

the FBI’s computer database are degraded in quality from a photograph of the

same print, which contributes to the ease of falsifying a match. 45

Fingerprint Identification Is So Inexact That Honest

Errors Occur

The ease with which fingerprint evidence can be

deliberately falsified by crime lab personnel is compounded by what could be

honest fingerprint identification errors. Possibly honest errors are known to

have led to the conviction of a number of innocent people. 46 One

of those was John Stoppelli, who was in

In light of what has

been learned in the intervening century, R. Austin’s Freeman’s 1907 detective

novel – The Red Thumb Print – has

proven to be prophetic. Its plot revolved around the perfect forgery of a thumb

print found in blood at the scene of a crime, that if

taken at face value would have sent an innocent man to prison. It is now known

that Mr. Freeman’s story was a cautionary tale about ascribing too much value

to seemingly incontestable fingerprint evidence.

The FBI Threw Caution To The

Wind In Going After Mayfield

In Brandon Mayfield’s case the FBI threw caution to the

wind. The degree to which the Bureau went to try to tag him as a participant in

the

Glaring by its omission, is

any allegation in Werder’s affidavit that Mayfield

had been observed or was otherwise known by anyone, whether a government agent

or informant, of being involved in any illegal activity whatsoever, much less

the four March 2004 bombings in

Mayfield Was Targeted Because He is a Muslim

If Mayfield had been a practicing Christian, or Jew, or

some faith other than Muslim, then actions attributable to his belief in that

religion set forth in an arrest/search warrant affidavit would not only have

failed to provide ancillary support for his arrest, but would have highlighted

the incongruity between his lifestyle and the FBI lab’s “conclusion of a 100

percent positive identification” his fingerprint matched the incriminatory one

on the plastic bag in Spain. 53

Muslims are suspected

of executing the

The importance of the

affidavit’s emphasis on Mayfield’s religious affiliation is indicated by his

lack of involvement in any criminal activity. This is supported by the

assertion of

Brandon Mayfield’s arrest as a material witness

depended on a federal judge being convinced by FBI agent Werder’s

affidavit to sign the warrant. To be convincing, the affidavit relied on the

reader’s predisposition to be prejudiced against Muslims. Hence the government

proceeded on the assumption that the judge the warrant was presented to, in

this case U.S. District Court Judge Robert Jones, would share that prejudice

and overlook the affidavit’s inconsistencies and insubstantiality.

After his release,

Mayfield expressed his opinion that his religious orientation was why the FBI

selected him, “I believe I was singled out and discriminated against, I feel,

as a Muslim.” 56 The FBI, however, couldn’t have done anything without

willingly being backed up by federal prosecutors and federal Judge Jones.

Federal Judge Robert Jones Failed To Perform His

Constitutional Gatekeeper Responsibility

Thus while it is easy to blame the FBI and the US

Attorneys Office in Portland for proceeding without caution – Judge Jones must

shoulder ultimate responsibility for failing to perform his constitutional

gatekeeper function to shield the rights of an American from over-zealous

government agencies and employees. After all, the affidavit states, “MAYFIELD’s passport expired on October 20, 2003 and he is

not on record for renewal.” 57 It additionally

states, “Checks through the National Tracking System going back one year do not

show any airline travel or border crossings by BRANDON MAYFIELD…” 58 The

affidavit then surmised that since there was no record of his international

travel, “it is believed that MAYFIELD may have traveled under a false or

fictitious name, with false or fictitious documents.” 59 However

a number of obvious facts undermine that supposition. The FBI’s intense seven

week investigation of Mayfield from March 21st to May 6th didn’t uncover any

proof of any kind he had traveled out of the country at any time during the

previous several months, or that his whereabouts were unaccounted for during

any several day period of time it would have taken him to stealthily travel to

Spain, participate in the bombing’s execution, and then return to the U.S.

without a single client, associate, friend or family member noticing his

prolonged and unusual absence.

The affidavit’s

attempt to paint Mayfield as guilty by portraying unremarkable actions and

associations related to his Muslim faith as sinister, coupled with its attempt

to gloss over the lack of any evidence he had ever traveled to Spain, combined

with the concealment that the SNP’s comparison of his

print to the one on the plastic bag was “conclusively negative,” points

directly to the FBI’s deliberate attempt to frame Brandon Mayfield as involved

in the Madrid bombing. The apparent purpose of FBI agent

Werder’s affidavit wasn’t to set out a s

The evidence in the public domain indicates that Judge

Jones didn’t seriously question the affidavit’s inconsistencies from May 6th

when federal prosecutors requested he authorize Mayfield’s arrest, to May 24th

when he ordered Mayfield’s release from federal custody. So the most charitable

description of Judge Jones’ actions is he allowed himself to be duped into

rubber stamping the government's request to have Mayfield arrested, when a

cursory examination of the affidavit offered to justify Mayfield’s arrest as a

material witness would have revealed significant, if not fatal flaws

undermining the allegation he was an international terrorist. Although it fell

on deaf ears, Mayfield had plainly spoken the truth at his first court hearing

when he told Judge Jones, “That’s not my fingerprint, your honor” 60

Mayfield Was Saved By The

Spanish National Police

With a compliant federal judge giving a free hand to

the FBI and federal prosecutors, it was sheer luck that Brandon Mayfield was

saved from possible prosecution for a capital crime by the Spanish National

Police crime lab’s independent analysis of his print. He was also fortunate

that the SNP refused to cave into the FBI’s intense pressure to back up their

identification of Mayfield. Carlos Corrales, commissioner of the SNP’s science division, said the FBI “called us constantly.

They kept pressing us.” 61 Mr. Corrales

was perplexed by the FBI’s desire to pin the bombing on Mayfield, saying “It

seemed as though they had something against him, and they wanted to involve

us.” 62 It was also

fortuitous for Mayfield that the SNP’s exclusion of

him as a suspect attracted international media attention that

As Mayfield’s

attorney, federal public defender Steven Wax commented, “But for the unusual

circumstance of another national police agency conducting its own independent

investigation, Mr. Mayfield would still be incarcerated.” 63 Mayfield’s

other attorney, federal defender Chris Schatz, openly wondered how many people

didn’t have a White Knight to save them from a police crime lab’s false

fingerprint ID, “Who knows how many people are sitting in state and federal

prisons that have just never come to light because there is no independent

agency like the Spanish National Police.”

64

The answer to “how many” people have not been as lucky

as Brandon Mayfield is unknown. However it is known that many innocent people

have been victimized by a fingerprint misidentification during the past

century, and that a number of inescapable human and scientific reasons underlie

such errors. So prudence and a sense of fair play dictates the fingerprint ID

of every suspect should receive the same intensity of independent scrutiny that

prevented Brandon Mayfield’s possible wrongful conviction as a terrorist.

The day of his release,

Brandon Mayfield shared what he believed was the meaning of his experience for

all Americans, “You can’t trade your freedom for security. Because

if you do, you’re going to lose both.” 65

Endnotes:

1 Transcripts Detail Objections, Early Signs of Flaws,

Les Zaitz, The Oregonian,

May 26, 2004.

2 FBI Admits Fingerprint Error, Clearing Portland

Attorney, David Heath and Hal Bernton (staff),

Seattle Times, May 25, 2004.

3 Affidavit of Rickard K. Werder, May 6, 2004, In Re:

Federal Grand Jury 03-01, No. 04-MC-9071 (USDC WD OR), ¶ 7.

4

5

6 Id at ¶ 8.

7

8 FBI Admits Fingerprint Error, supra.

9 Spain and U.S. at Odds on Mistaken Terror Arrest,

Sarah Kershaw (staff), New York Times, National Section, June 5, 2004. (

10

11

12 Affidavit of Rickard K. Werder, supra at ¶ 8.

13 Spanish Investigators Question Fingerprint

Analysis, supra.

14 FBI Admits Fingerprint Error, supra.

15

16 FBI’s Handling of Fingerprint

Case Criticized, David Heath (staff), Seattle Times, June 1, 2004.

17

18

19 FBI Apologizes to Mayfield, Noelle Crombie and Les Zaitz (staff),

The Oregonian, May 25, 2004.

20 Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and

Criminal Identification, Simon A. Cole,

21 Advances in Fingerprint

Technology, Second Edition, Ed. By Henry C. Lee and R.E. Gaensslen, CRC

Press, 2001, p. 383. (emphasis added).

22 Suspect Identities, supra at 81.

23 Finger Prints, Francis Galton,

London, Macmillan and Co., 1892, pp. 65-66.

24 Wallace Defends Fingerprint

Remark, BBC News, September 18, 2002,

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/scotland/2265693.stm (last visited June 6,

2004).

25

26 See e.g., Scientific Methods, McGraw-Hill

Encyclopedia of Science & Technology, 1997, Vol. 16, p.119-120 (Among the

requirements of the scientific method are: “testable consequences;” “repetition

of the test;” and “reliability and accuracy.”).

27 Suspect Identities, supra at 202-203

(“pseudo-science”).

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44 These Are Definitely Not Scully’s Breasts: Inside

One Man’s Crusade To Save Gillian Anderson and the

rest of the world from the plague of fake celebrity porn, by David Kushner,

Wired Magazine, November 2003, pp. 142-145.

45 This degradation occurs from a combination of the

scanning process used to digitize them and the 12.9 to 1 compression ratio used

when they are convert into the WSQ file format used by the FBI to store

fingerprints in its database.

46 See e.g., The Innocents Database,

http://forejustice.org/search_idb.htm, which lists a number of people whose

wrongful conviction was contributed to by an erroneous fingerprint ID.

47 Never Plead Guilty: The Story of Jake Ehrlich, John

Wesley Noble and Bernard Averbuch, Farrar, Straus and

48

49

50

51 Affidavit of Rickard K. Werder, supra at ¶ 23. (See also, Spain Bombing Glance, Associated Press, Seattle

Post-Intelligencer, May 24, 2004.)

52

53

53 FBI Case

54 FBI Case

55 FBI Case

56

57 Affidavit of Rickard K. Werder, supra at ¶ 21.

58

59

60 Transcripts Detail Objections, Early Signs of

Flaws, Les Zaitz, The

Oregonian, May 26, 2004.

61

62

63 FBI Apologizes to Mayfield, supra.

64

65 ‘Sneak and peek’ searches dogged family, Joseph

Rose (staff), The Oregonian, May 25, 2004. Mayfield’s comment is reminiscent of

an observation credited to Benjamin Franklin, “They that can give up essential

liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor

safety.”