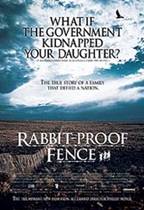

Rabbit-Proof Fence

Review by Hans Sherrer

For Justice Denied Magazine

April 10, 2003

Starring

Everlyn Sampi as Molly Craig;

Tianna Sansbury as Daisy Craig; Laura Monaghan as Gracie; David Gulpilil as Moodoo;

Kenneth Branagh as A.O. Neville

Directed by Phillip Noyce

Screenplay by Christine Olsen

Produced by Phillip Noyce, Christine

Olsen and John Winter

Music by Peter Gabriel

Released in the U.S. by

Miramax in November 2002. To be released on video and DVD in the Summer of

2003.

Rated PG, 94 Minutes

Based on the book Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris

Pilkington (1996)

Rabbit-Proof Fence is a movie phenomena.

It was shown as a first run feature in major cities such as Seattle for months,

even though it is a low budget Australian film with no major stars, no special

effects, no foul language or sex scenes, no explosions and no mega ad campaign.

Audiences flocked to see the movie when the simplicity of the true story it

tells can be summarized in twenty words: In 1931 Australia three young girls forcibly

taken from their families escaped and endured many hardships trying to elude

capture. What is captivating about Rabbit-Proof

Fence is the hard to believe details of the girl’s story.

In 1905 the

Australian government passed legislation authorizing the forcible removal of children

with a Caucasian father and an Aboriginal mother from their Aboriginal families

and their confinement in a Native re-education center. Known as half-castes,

the children were taught rudimentary English and the manners necessary for them

to fit into Caucasian society. The children were also taught how to perform

menial jobs. Boys were trained to do manual labor and girls were taught to be a

domestic servant. It was calculated that after a couple of generations of

breeding with only Caucasians, the Aboriginal genes of female half-castes would

be diluted to the point that their offspring would appear to be Caucasian. The national

goal of the removal policy was to maintain two distinctly identifiable ethnic

groups. Areas from which all half-castes had been removed were described as

“cleaned up.” [1]

Under the

legislation the Chief Protector of the Aborigines was entrusted with the power

of being judge, jury and executioner by deciding which children would be forever

taken from their home. Their summary decisions were not subject to judicial

approval or review. From 1915 to 1940 career bureaucrat A.O. Neville held that

position in Western Australia. Neville knew nothing about Aboriginal life, and

he shared the blatantly racist attitude of a predecessor, James Isdell, who compared

the taking of Aboriginal children from their families to the separation of a

pup from its mother. His open contempt for Aborigines and comparison of them to

dogs was reflected in official correspondence in which he wrote, “All

Aboriginal women are prostitutes at heart,” and all Aborigines are “dirty,

filthy, immoral.” [2]

Those attitudes were the norm among the people assigned by the Australian

government to act as the Aborigine’s Chief Protector.

The three

girls whose story is told in Rabbit-Proof

Fence were half-castes living in the Jigalong settlement in the Northern

part of Western Australia’s outback. In 1931 Chief Protector Neville signed an

order for the institutionalization of sisters Molly and Daisy Craig and their cousin

Gracie at the Moore River Native Settlement north of Perth. The Australian

police duly snatched the screaming girls as they tried to run away, and they

were stuffed in the police car in front of their frantic mothers and other

relatives who could do nothing but wail uncontrollably and beat the ground, knowing

from experience they would never see the children again. Molly was 14, Daisy

was 8 and Gracie was 10.

Fifteen

hundred miles from Jigalong, Moore River was a de facto prison populated by innocent

children whose only offense was being born with a skin color unacceptable to

Australia’s Caucasian population. The children’s jailers considered them to be

the equivalent of dogs, and that is how they were treated. The conditions at

the Moore River “prison” were abominable. Misbehaving children/inmates could be

flogged and kept in solitary confinement for weeks in a windowless iron shed known

as the “boob.” The food was broth and bread, and

1/7th as much money was spent on the children/prisoners

at Moore River as on the upkeep of prisoners in Western Australian jails. In

1934, three years after the events

portrayed in the movie, a Royal Commissioner described the conditions at Moore

River as “woeful.” [3]

The children

at Moore River were expected to spiritually die under the guidance of their warders:

they were stripped of their family heritage and roots, their native language,

their customs, their home and way of life. In other words, they were deprived

of everything unique to them as Aborigines and expected to become second class citizens

to Caucasian Australians.

The prison was

guarded by the invisible wall of being in a remote location a vast distance

from the home of the child prisoners, and a crack Aboriginal tracker

methodically hunted down any child who dared to escape. Shortly after arriving

at Moore River the three girls watched a girl that had tried to escape put in

the “boog” after she was herded back by the tracker. Soon after that Molly led

the girls on a gutsy escape in broad daylight while everyone else was at a

Sunday church service. Molly knew the risks, but she was too heart-sick for her

family and home to stay at Moore River.

The Rabbit-Proof Fence then becomes a

fantastic tale of survival and escape. The girls were faced with a 1,500 mile

trek on foot – more than half the distance from Los Angeles to New York - across

inhospitable terrain to return home. At the same time they were battling fatigue,

the elements, and scrounging for food and water, they used their wits to elude

capture by the Australian police and the relentless tracker. As their run for

freedom stretched from weeks to months, the efforts of A. O. Neville and the

Australian government to capture them became ever more frantic.

Molly and Daisy escaping along Western Australia’s rabbit-proof fence

As straightforward

as its plot is, Rabbit-Proof Fence

defies simple categorization because it can be viewed in so many different ways.

It is an intense human drama, it is an inspiring tale of raw grit and ingenuity

in the face of overwhelming adversity, it is a passionate story of the love

shared by family members, it portrays the casualness with which people will treat

others inhumanly, and it warns of the danger of empowering bureaucrats to indiscriminately

designate people to be treated as criminals.

Amazingly, the

Australian government continued kidnapping half-castes from their homes until

1970. After that many Australians were so ashamed of having done nothing to

stop thousands of innocent children from being torn from their families that

they denied it ever happened. Rabbit-Proof

Fence obliterates that delusion.

Based on a

book written by Molly’s daughter, Doris Pilkington, Rabbit-Proof Fence is an example that even with a mostly unknown

cast and small budget, a powerful story well told can mesmerize an audience. I

saw the movie in a packed theater and there were stretches of many minutes when

you could have heard a pin drop.

Molly and her

sister Daisy, who are now in their 80’s, appear briefly at the end of the movie.

Rabbit-Proof Fence is a testament to their

incredible fortitude as children, and their unintentional defiance of the

Australian government’s unforgivable and unconscionable mistreatment of thousands

innocent children.

Rated PG, Rabbit-Proof Fence is a movie experience

that is unlikely to be disappointing, whether someone is 10 or 80, and whether

it is seen in a theater or when released for home viewing.

THE END